Cybercriminals and spies working for nation-states are surreptitiously coexisting inside compromised name-brand routers as they use the devices to disguise attacks motivated both by financial gain and strategic espionage, researchers said.

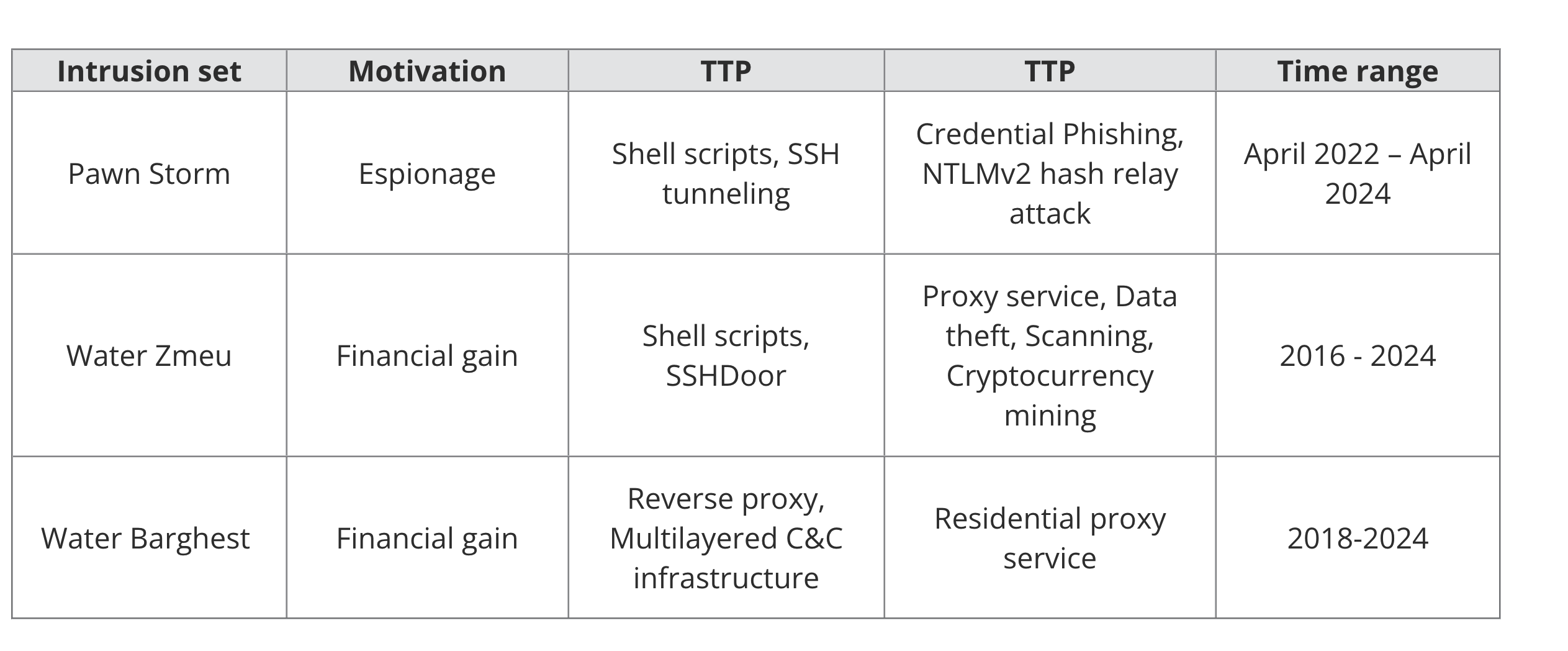

In some cases, the coexistence is peaceful, as financially motivated hackers provide spies with access to already compromised routers in exchange for a fee, researchers from security firm Trend Micro reported Wednesday. In other cases, hackers working in nation-state-backed advanced persistent threat groups take control of devices previously hacked by the cybercrime groups. Sometimes the devices are independently compromised multiple times by different groups. The result is a free-for-all inside routers and, to a lesser extent, VPN devices and virtual private servers provided by hosting companies.

“Cybercriminals and Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) actors share a common interest in proxy anonymization layers and Virtual Private Network (VPN) nodes to hide traces of their presence and make detection of malicious activities more difficult,” Trend Micro researchers Feike Hacquebord and Fernando Merces wrote. “This shared interest results in malicious internet traffic blending financial and espionage motives.”

Pawn Storm, a spammer, and a proxy service

A good example is a network made up primarily of EdgeRouter devices sold by manufacturer Ubiquiti. After the FBI discovered it had been infected by a Kremlin-backed group and used as a botnet to camouflage ongoing attacks targeting governments, militaries, and other organizations worldwide, it commenced an operation in January to temporarily disinfect them.

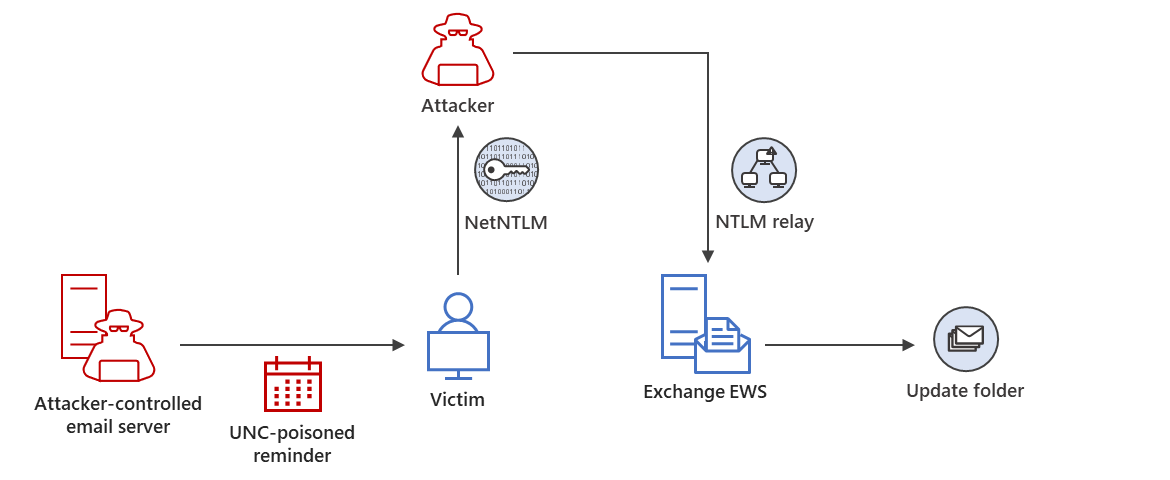

The Russian hackers gained control after the devices were already infected with Moobot, which is botnet malware used by financially motivated threat actors not affiliated with the Russian government. These threat actors installed Moobot after first exploiting publicly known default administrator credentials that hadn’t been removed from the devices by the people who owned them. The Russian hackers—known by a variety of names including Pawn Storm, APT28, Forest Blizzard, Sofacy, and Sednit—then exploited a vulnerability in the Moobot malware and used it to install custom scripts and malware that turned the botnet into a global cyber espionage platform.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...